Fritz Lang bailed out on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to work on Die Spinnen (aka The Spiders), and when Robert Wiene took over the project he opened the doorway to feature films that incorporate the flashback setting, the horror setting, and this still being the greatest example of German Expressionism. With its Lovecraftian styled architecture, its political standings and satire of the German government, and the pale-faced psychopathic somnambulist from hell, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari stands among the best horror films to ever have been made.

Of course having read the blood chilling origins of the Caligari tale, we know that Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer did not write a screenplay about a government that brainwashes and puppeteers its citizens, and there is no Nazi symbolism here either. The Nazi party was formed in 1933 and this film was made between the years of 1919 and 1920, for starters.

According to Wikipedia, in 1913 Janowitz had the unfortunate luck of witnessing a stranger exit a row of bushes and disappearing into the shadows of the night. The next morning a young woman’s body was found ravaged. He told that tale to Mayer and it scared them stiff. Also, many times they would enter a fair and one night they had witnessed a sideshow called “Man and Machine”, in which a man did feats of strength and predicted the future, supposedly under hypnosis. They combined those elements into a horror film screenplay and tried to get Erich Pommer to green light the production. After hearing the origin tales he was convinced and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was underway.

Werner Krauss plays the deranged Dr. Caligari and he approaches a fairground in the mountain village of Holstenwall. He appeals to present his performance in the fair and receives a grant. That night, the audience of the fairground witnesses a pale, mushroom cut, somnambulist, played creepily by Conrad Veidt, who apparently had been sleeping for 23 years; and he can also foretell the future. He exclaims that someone in the crowd will die before sunrise, and boy is he right. That night the protagonist’s (Francis, played by Friedrich Fehér) best friend is murdered in his own bed.

The somnambulist (Cesare) and Dr. Caligari are not immediately suspected because there are rumors around of a serial killer on the loose as is. Was Caligari using that knowledge as a front for hiding his own murders?

Cesare looks creepy. He wears full body black spandex and walks like a marionette, but without the strings. He has deep penetrating black circles around his eyes and they hypnotize and creep people out.

One morning the lovely Jane, an acquaintance of Francis, ventures into the fairgrounds and bumps into Dr. Caligari; he decides to showcase Cesare to her. Encased in a vertically erect coffin, Cesare opens his eyes and stares into those of Jane. He becomes entranced and she frightened. She runs off. That night Francis decides to spend the night outside of Caligari’s house to monitor him and the somnambulist. Plausibility unbeknown to anyone, Cesare pays Jane a visit at the same time and kidnaps her. A chase ensues: Cesare with Jane in his arms, clinging to walls in the streets and almost dancing freakishly, the police hot on his tail. The morning comes and he passes out letting go of Jane. Francis cannot believe that Cesare is caught because he was sleeping inside his coffin the entire night. He must have been!

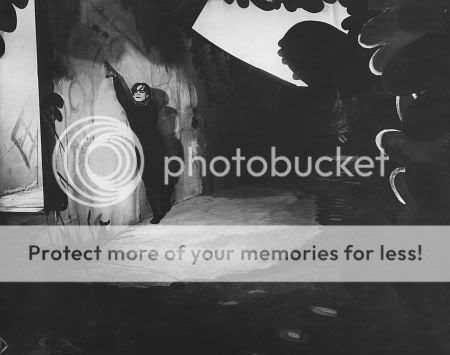

Now that I got your attention that is all that I will say about the story. The origins and ideals of German Expressionism work mainly through the actors’ body language and strange architectural backgrounds. Usually, a tormented soul or dementia is involved, much like in this classic film. Seeing that the film opens in an insane asylum and that the story is told though the flashbacks of Francis, one can only guess what goes on in his noggin.

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) is another great, classic example of German Expressionism but it’s not a horror film so dementia in not present. The actors throw themselves around the sets; they throw their arms towards the heavens and decree that something is wrong with the system and must be righteous again. Rudolf Klein-Rogge plays professor Rotwang, the evil scientist that built the man-machine (an early version of an android). Equipped with black leather gloves and wild white hair he throws his right hand toward the heavens in a cry of insanity, clutching his heart with his left, many times throughout the film. You can smell the passion that the actors portray and especially the one of Gustav Fröhlich.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was seen by many, probably millions, by now and is almost unanimously a great example of its genre. By today’s standards the makeup in the film is dodgy and the sets look like bristol-paper cutouts, which they were. But the film is terrifically atmospheric and, for the most part one does not notice the “fakeness” of it. There is no perfect angle or a straight line, per se, in this film. Windowpanes are crooked as are the houses themselves. One almost feels confined and prays that another’s house will not fall on them. But the crooked architecture in the disturbed psyche stands on its own and frightens its citizens by remaining as is. There is also a great use of shadow-play in this film, reminiscent of Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922.) Seeing a tall shadow creep along a wall, disembodied and alone until the creature, its master emerges into frame. The creature is more frightening than its shadow. That was Count Orlock (played cautiously and mysteriously by Max Schrek), that was Cesare (Conrad Veidt), and even now they are The Strangers from Dark City (Richard O’Brien, Ian Richardson, and Bruce Spence).

Film noir, another film genre that I love, needs to provide special thanks to German Expressionism: Dutch angles, superimposed shadows, lots of night scenes, and the feeling of dread and evil around the corner. German Expressionism will live on as a lesson in atmosphere and silent storytelling. Visually grand and rich in character, Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924), Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) are long going to fill voids and enter uncorrupted minds alongside this pinnacle of perfection, that is The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. And Cesare will never be forgotten; like his successors Gwynplain (also played by Conrad Veidt in Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs (1928)) and The Joker (from the Batman series).

No comments:

Post a Comment