I have a feeling that for as long as I live, the two greatest film of all time will always be Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941) and F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927). On a technical level both films bring out the impossible and although the techniques used today in standard filmmaking are different and more advanced, it still looked more impressive back then.

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans is the heartwarming and breaking story of a farmer (George O’Brien) who is unfaithful to his wife (Janet Gaynor). He has an affair with a city woman (Margaret Livingston) and she is wicked; wearing her exotic city clothes just the right way, teasing him with fresh lipstick and promising to take him with her and live in the city. The farmer, of course refuses to leave and so she drops the bomb on him: she proposes the farmer drown his wife in the lake and run off with her. The thought of murder is extremely cruel and the farmer becomes angry. He strangles the city woman but then, ironically, realizes that he might just have it in him to do exactly what she had proposed. He yells at her and orders her to leave him be and takes a walk around the swamps surrounding his farm. The sun is fast approaching and he must make an important decision.

The farmer tells his wife in the morning that he would love to take her on a boat ride. She, suspecting his affair with the city woman through village gossip, still accepts his invitation believing that he has changed. While drifting in the river on the boat, the farmer stands erect and his angry fists reshape into claws. He approaches his wife, hands toward her throat and with a wild look in his eyes...

She yells and he awakens. Recognizing the look on her simple but dainty face, he feels like the worst human being on the planet and immediately begs her for forgiveness. He rows the boat to the nearest shore and she runs off. He takes chase. They arrive in The City. After almost being run over by several cars the farmer protects his wife and they proceed to have the greatest day of their lives.

In 1926 Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau moved to the United States. After receiving critical praise for his film The Last Laugh (1924) he was given carte blanche and Sunrise was his first American film; but unlike Orson Welles, he did not lose his career afterwards. It was worse than that, actually because he was killed in a car crash in 1931, four years after the release of Sunrise.

Sunrise has stood the test of time because when Hollywood was fast approaching the talkies, many directors still wanted to continue making films in the silent form; but most had wanted to transfer over and quickly. Talkies first appeared in 1927 with The Jazz Singer and by 1930, the whole world was aware of the phenomenon. Charles Chaplin released City Lights in 1931, still as a silent film, and the whole world was astonished that he didn't conformwith the times. However, it was still viewed as amasterpiece and rightly so. It's also, still considered to be his best film, and one of the best silent comedies of all time.

Many call Murnau the master of German Expressionism and his greatest ally, and competition, was Fritz Lang (the discussion is still raging on). Most still prefer the artistic style of Murnau because Lang's films were either too farfetched or had too much overacting (if that's even possible). Try comparing M (1931) to Nosferatu (1922): you can't. I say they're like apples and oranges. They're both of the same medium but are of different species.

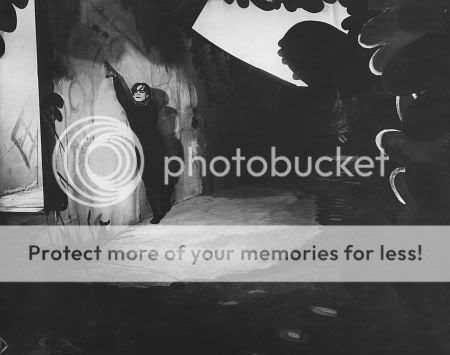

The cinematography here is worth noting even today, because some shots seem impossible. How can one possibly dolly track while in a swamp? Well, Charles Rosher, Karl Struss, and Murnau had figured it out that they could use a platform that hovered over the swamp while the camera was locked onto it, and the platform was suspended by strong cables. There are also plenty of forced perspective shots, much like how Lang shot Metropolis (1926). Mirrors were strategically placed around the sets providing the illusion that certain people were on different areas in the frame, and sets that were much smaller than others were also placed in the background of certain shots. Those sets physically got smaller as you walked through them. Sometimes midgets were used for wide shots from afar (like the airport runway in Casablanca).

If Citizen Kane is the textbook on how to make films, then so is Sunrise. Kane is as much a special effects picture as Sunrise and even though Sunrise lacks sound it still gets the job done, containing a strong emotional core through brilliant, atmospheric cinematgrpahy and powerful, reliastic performances.

In 1929, the first ever Oscars Ceremony was held and Sunrise won 3 awards in the categories of Best Cinematography (Charles Rosher, Karl Struss), Best Actress In a Leading Role (Janet Gaynor - who'd also won two other Oscars that year for Seventh Heaven and Street Angel), and Best Unique and Artistic Production (Best Picture).

Every time that I watch this film I see something new in it. Whether it's a gesture that someone makes or a camera movement I had missed before, Sunrise feels new every time. And just remember: this is an American film with an American cast and it was directed by F.W. Murnau, who directed and conceptualized Nosferatu (1922) and Faust (1926). It's more than just a triumph it's an important film, and it will always provide audiences with the emotions that they forgot they once had.